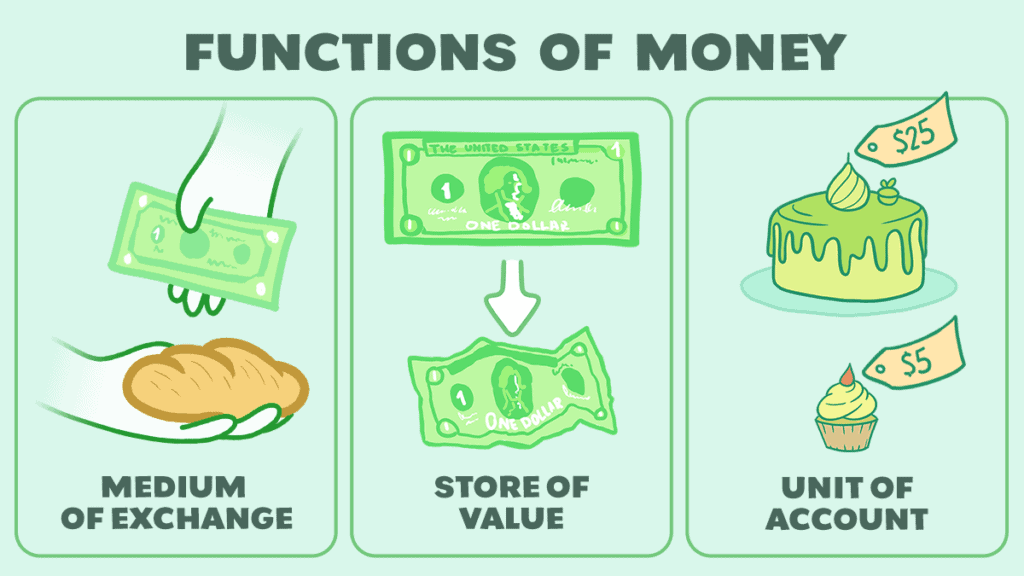

If you’ve ever read one of these articles before, you probably know that money is anything that serves three basic functions—it is a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account.

As such, money has value. It can have either intrinsic value, like commodity money such as gold, which is valuable in and of itself, or only extrinsic value, like fiat money such as the US dollar, where it is valuable only because others are willing to accept it as having value.

Either way, no matter what form it takes, money can be said to have value.

What if, instead of having either intrinsic or extrinsic value, something merely acted as a stand-in for something of value? In other words, instead of exchanging gold or dollar bills, you gave somebody a piece of paper that entitled them to the item of value.

Would this still qualify as money? Yes—as long as it serves the three functions of money. What we’ve just described is known as representative money.

Representative money is any instrument used as a medium of exchange that represents something of value—specifically commodity or fiat money—and can be exchanged for the item of value on demand.

In this article, we’ll look at how representative money works, various forms of representative money throughout the ages, and its advantages and disadvantages.

How Representative Money Works

In a lot of ways, representative money works like an IOU. It represents the commodity or fiat money that one intends to transfer to another party. It does not actually transfer that currency to the other party; however, it entitles them to payment in the form of the relevant currency at a later date.

In fact, some of the earliest forms of paper money issued by European governments were exactly that.

As European governments began to set up colonial governments in North America, the shipping time between the mother country and their colonial counterparts often resulted in colonial governments running out of cash. As a result, colonial governments would issue “I Owe You”s (IOUs), which were then used as currency.

The first example of this occurred in 1685 when the French colonial government issued playing cards with a monetary denomination signed by the governor to soldiers as payment.

The soldiers then exchanged these cards for goods and services within the colony. However, they represented French coinage and could be exchanged for French coins once the government had the resources.

A more modern example would be a check. If you think about it, a check is nothing more than an acknowledgment that you owe someone money, and a promise to pay. It doesn’t actually give them the money—it simply authorizes the bank to transfer the money to them at a later date on your behalf.

To get a better understanding of representative money, let’s explore the various forms it has taken throughout the ages.

History of Representative Money

Representative money goes back almost as far as civilization itself. Temples in ancient India, Egypt, and China often had commodity warehouses where people could store their valuables.

Upon storing an item of value, the temple would issue its owner a Certificate of Deposit claiming ownership of their portion of the goods stored in the warehouse. This certificate could then be exchanged in place of having to exchange the goods themselves.

Going back to hunter-gatherer times, some of the earliest commodities used as money were animal furs and skins. Rather than carry all the fur or skins with them, which could get bulky, potential traders would take a cutting from the skins as a representation of and proof of ownership of the entire stock.

They would then use this to trade as the ownership could be verified by matching the cuttings with the holes left in the rest of the skin. Rome, Carthage, and China are all known to have used such leather cuttings as a medium of exchange within their civilizations.

In a similar fashion, precious metals were first minted into coins by the Kingdom of Lydia in the late 600s BCE, and this practice was replicated by the Roman Empire and followed in Europe up until the Middle Ages.

At this point, banks began to emerge that would offer notes that could be exchanged for their equivalence in precious metals on demand.

These notes would be carried around and used for day-to-day transactions. In the same way that it was more convenient to carry around leather cuttings than the entire animal skin, people found it convenient to deposit their gold in banks and conduct daily business with paper notes.

The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard

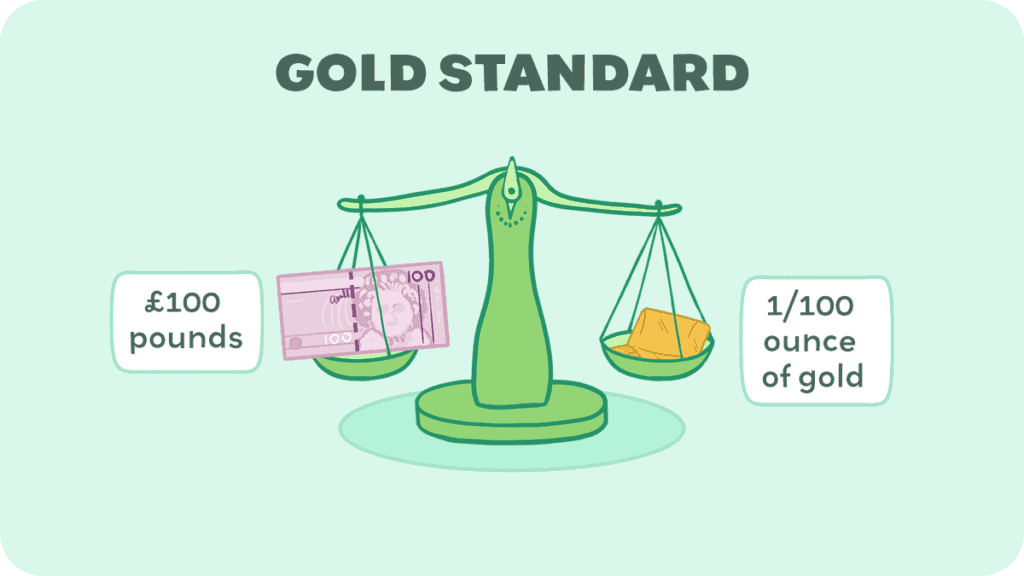

The heyday of representative money came during the Age of the Gold Standard. Starting with England in 1819 and quickly followed by the United States in 1834, countries printed currency linked to a fixed quantity of gold.

This was joined by other major countries, including France and Germany, by the 1870s, and held until World War 1, during which time countries ended the convertibility of their currency to gold to meet the spending demands of the war.

Though briefly restored during the interwar period, the demands of the Great Depression again caused countries to abandon the Gold Standard and, by extension, representative money in favor of fiat money.

Following the Second World War, forty-four Allied countries met at Bretton Woods in an attempt to revive the Gold Standard. Under this agreement, the United States would fix its dollar to gold and the other countries would fix their currency to the US dollar. This created a kind of vicarious Gold Standard.

It also marked the return of a system of representative money where the currency of each nation in the agreement represented a fixed amount of US dollars and each US dollar represented a fixed amount of gold.

However, as other economies recovered and grew, the US economy became responsible for a smaller and smaller percentage of global production—therefore, demand for US dollars decreased.

At the same time, the US government made massive investments in both foreign aid (for example, with the Marshall Plan) and in military spending as the Cold War heated up. By the 1960s, the US gold supply could no longer meet the global supply of US dollars—that is, if everyone tried to convert their dollars to gold at once, the United States would be insolvent.

To prevent this looming run on gold, President Nixon temporarily removed the United States from the gold standard in 1971, and made the change permanent in 1973. This marked the end of the era of representative money as the primary national currency and ushered in the age of fiat money—money that isn’t backed by anything other than the word of the government.

Advantages of Representative Money

The first and most obvious advantage of representative money, and its reason for existence in the first place, is its convenience. It is easier to deposit your wealth in a bank or other depository, such as ancient Egyptian temples, and simply use paper bills or notes to conduct transactions instead of carrying around several pounds of gold.

Even with fiat money today, most people prefer to keep their money in a bank and use checks or cards for payments as opposed to carrying around duffel bags full of cash like Tony Soprano.

Another advantage is confidence. Since money is primarily a medium of exchange, it is only useful when people are willing to accept it as payment for goods and services. People are only willing to accept it when they have confidence that it will continue to be worth something in the future.

Because representative money is backed by something of intrinsic value, people can have confidence that it will be worth something, even if their confidence in the government is shaky. In a worst-case scenario, they can always exchange their representative money for the commodity itself.

Disadvantages of Representative Money

Of course, this last point is only true if people believe the issuer will honor their word to convert their representative money into the backing commodity.

If people begin to lose confidence in the willingness or ability of the issuer to convert their money into gold (or other commodity), many people may demand the conversion of their representative money all at once. This is known as a run and can cause major economic problems, including complete economic collapse.

Remember, it was the fear of such a run that led the United States to abandon the Bretton Woods system.

Additionally, compared to fiat money which can simply be printed, representative money must be backed by a commodity. Therefore, producing more of the money requires producing more of the commodity.

Depending on the commodity, this can be expensive and time-consuming, if it’s possible at all.

For example, gold must be mined, which involves discovering gold deposits, setting up mining operations, and then carrying out those operations. If no new gold deposits can be found or acquired, then no new money can be produced.

Conclusion

Representative money has been used throughout history largely due to its convenience. Much of the time, it has been backed by a commodity. However, today’s forms of representative money such as checks or money orders represent fiat money that has been deposited with an institution.

Still, even with no commodity backing it, people find it more convenient to conduct most of their transactions with these instruments as opposed to the physical currency issued by their national bank.

We hope that you found this article informative. We invite you to check out our other articles, subscribe, and we hope that you’ll join us again.