What is money? Is it a physical thing? Is it an idea? We know there are many types of money, from shells to pieces of paper, to bits on a computer, but practically, what is it?

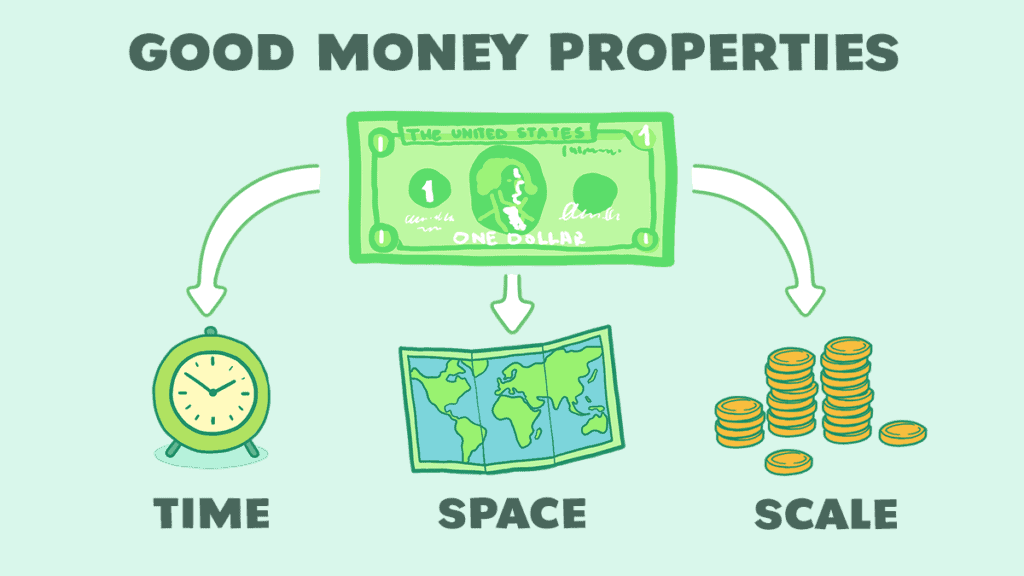

Money is an item or record that is an accepted payment for goods and services. It exists as a way to transfer value through space, time, and scale.

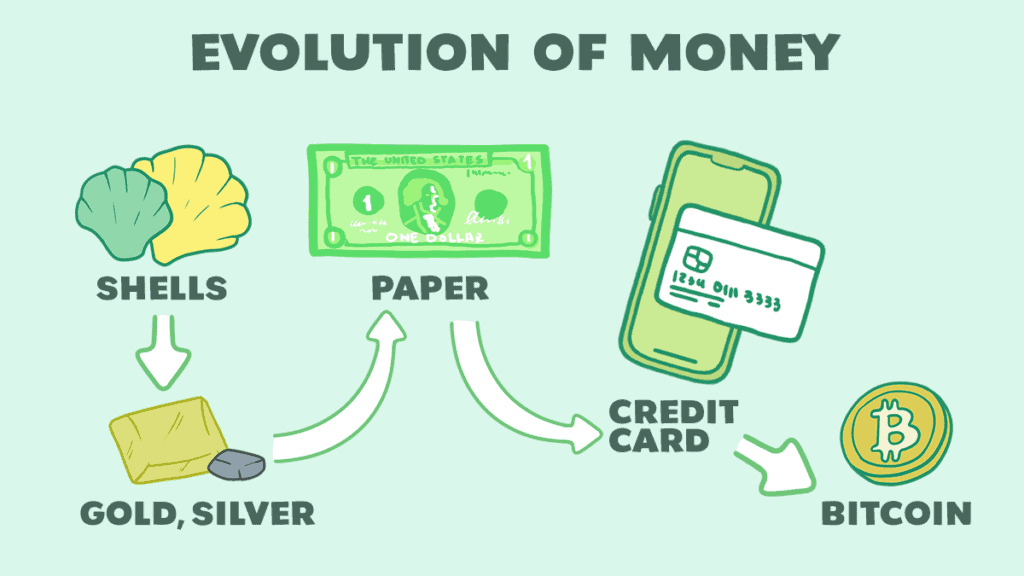

It turns out that money can be almost anything… throughout history, people have used cowry shells, dolphin teeth, cacao beans, and salt as money. The most common materials are precious metals, such as gold and silver. In the past century, paper money has become the most common, at least up until 1971 paper money was backed by a government supply of precious metals (The Gold Standard).

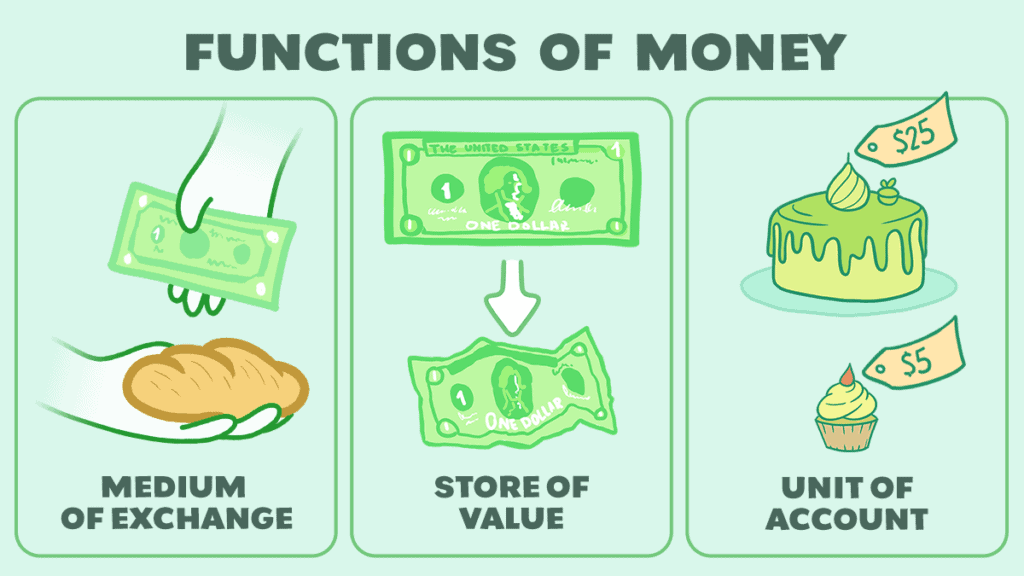

Functions Of Money

So, why would everyone go along with this? After all, a piece of paper by itself has little or no intrinsic value. You can’t eat it, you can’t build with it, and it doesn’t work well as clothing. However, if that piece of paper has George Washington or Ben Franklin’s face on it, you can get almost anyone’s attention.

It’s because money serves three very important functions in society:

- Medium of exchange

- Store of value

- Unit of account

Let’s explore these three functions one at a time and consider what would happen if society didn’t have money.

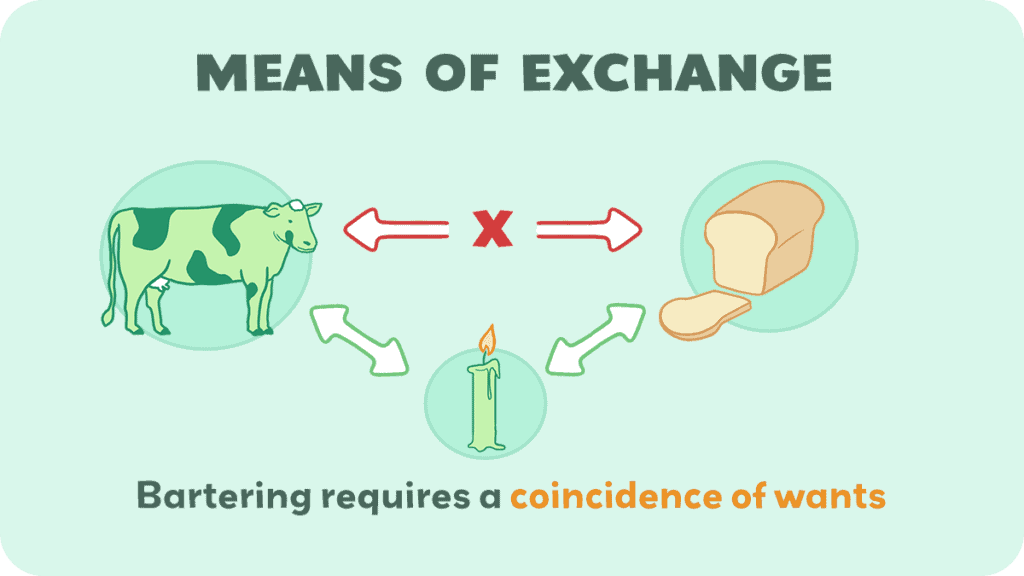

Means of Exchange

First and foremost, money is a means of exchange. This is a fancy way of saying that it can buy stuff. If you want something, all you have to do is pay an agreed-upon amount in exchange for that item. What if we didn’t have money?

Imagine you’re in a simplified economy of a butcher, a baker, and a candlestick maker. Say you’re the butcher. Imagine also that this economy doesn’t have money… you would have to use a barter system, the most primitive type of economy. This means trading goods and services directly for one another.

As the butcher, you have plenty of steaks, but you want some bread for a little balance. You go to the baker to trade some steaks for bread, but lo and behold, they’re a vegetarian. What do you do?

You now have to go to the candlestick maker, exchange steaks for candles, return to the baker, and trade your newly obtained candles for bread.

What if they don’t want candles? Maybe they already have plenty of light, maybe they’re blind, or maybe they have ugly kids they’d rather not look at. It doesn’t matter. The point is that you have nothing that the baker wants to trade for the bread you desire.

Remember, this is a simplified economy and already we’re seeing how complicated and difficult a barter system can be.

Now, let’s bring money into the equation. If all of you agree to accept one standard thing as money – say, cowry shells – the problem disappears. You can go to the baker and exchange cowry shells for the bread you want. It doesn’t matter that you have nothing that they want, since they can simply use the cowry shells to buy whatever goods or services they prefer.

Providing this means of exchange simplifies transactions and allows the economy to function smoothly.

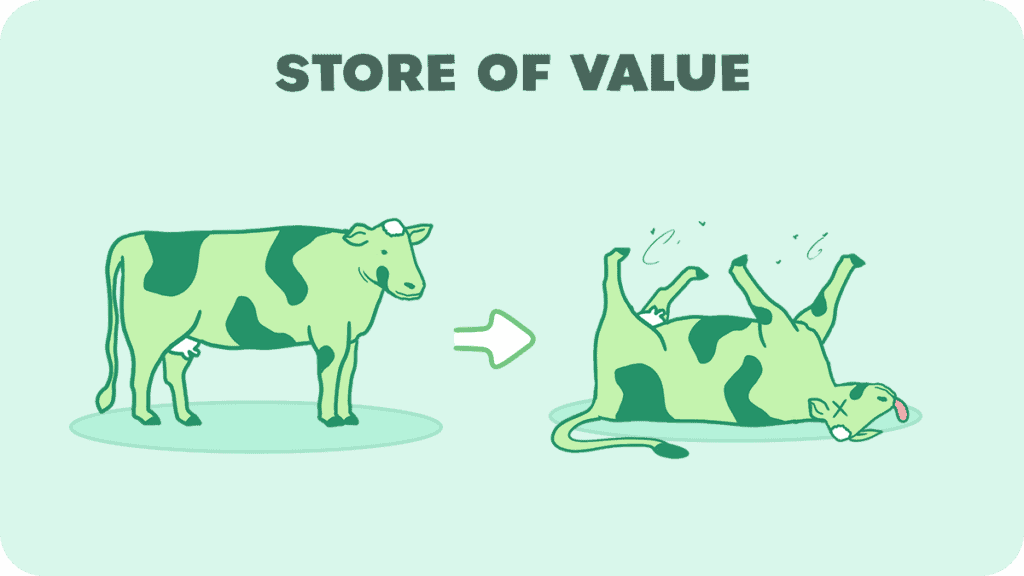

Store of Value

Secondly, money serves as a store of value. What this means is that people can save it and use it later. If you have $100 today, you can spend it, or you can keep it in your pocket or bank account and use it later. It won’t diminish in value. That $100 that you have today will still be $100 a year from now, though inflation may diminish the purchasing power. Likewise, other forms of money, such as cowry shells or gold, will maintain their value over time. As long as you don’t lose it, it will still be there in a year, five years, or ten years.

Let’s return to our simplified economy. You’re the butcher, and you butcher a cow. You have lots and lots of steak – more steak than you could ever eat. What do you do? In the barter economy, you’d have to trade all that steak relatively quickly. This could mean trading for things you don’t particularly want or accepting a low price for your steak. If you tried to save the steak, it would rot and become worthless. In other words, you’d have to spend it all immediately.

With money, you can sell the steak for money. True, you’d still have to sell it right away, but once it’s exchanged for money, you can hold onto it as long as you want. You could still go out and buy the things you want today, but if there’s nothing you want, you can also hold onto your money and spend it later. This also provides the protection of ensuring that you have something stashed away for a rainy day.

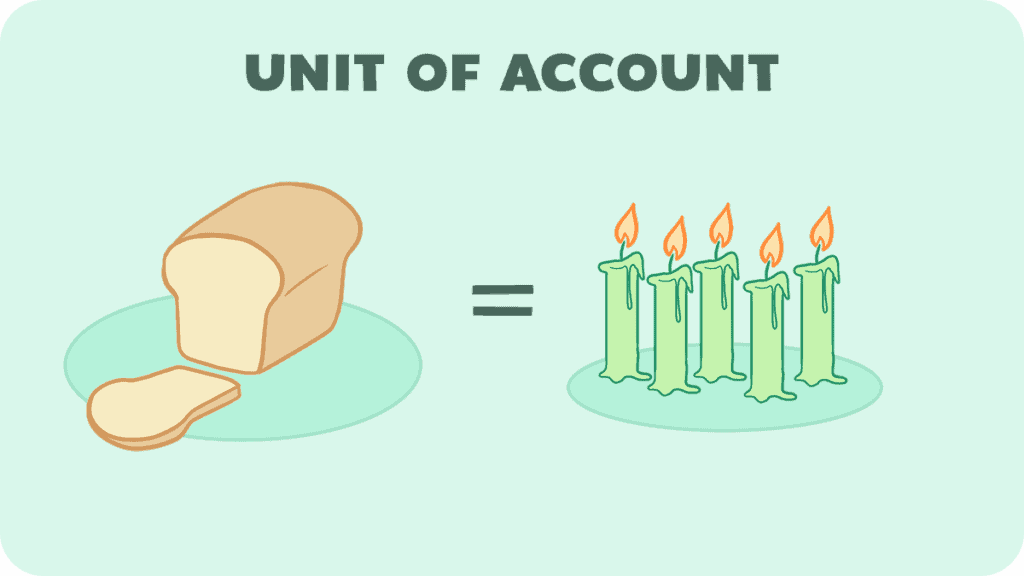

Unit of Account

Finally, money serves as a unit of account. Perhaps a better way of saying this is that it’s a unit that measures economic or monetary value in the same way that inches or centimeters can measure length and pounds or kilograms can measure weight. It provides a common language to quickly and effectively communicate how much something is worth or how much something costs.

Returning to our simplified economy, you know as the butcher that you make steaks. The baker makes bread and the candlestick maker makes candles (I suppose they technically should make candlesticks, but we’re going to say candles). How many loaves of bread is one steak worth? How many candles is a loaf of bread worth?

Even in our simplified economy, we’re already dealing with three units of account. In this model economy, we could probably figure the conversions out, but it would get really messy really quickly in a real-world economy with numerous goods and services. Money provides a common unit of account to simplify this, which can help in a variety of ways, such as pricing and purchasing decisions.

Instead of saying one steak equals 10 candlesticks equals 2 loaves of bread, we can simplify it by saying a steak is 10 shells, a candle is 1 shell, and a loaf of bread is 5 shells. Now we can measure how much value is in a steak, a candle, and a loaf of bread, without comparing them to each other.

What Makes Good Money?

So, what makes good money? As we’ve already mentioned, literally anything can be money so long as people agree to treat it as such. However, some things make better forms of money than other things.

Whether something functions well or poorly as money depends on how well it suits the three functions of money – how convenient it is to use as a means of exchange, how stable it is, and how easily it is to translate it to the price of other goods or services.

Another way to think of these 3 functions are to think about transporting value across time, space, and scale. Can we move the value of a steak across a year? Can we easily move the value of 500 candles without actually having to move them? And can we scale the value of a loaf of bread into slices? Money is a tool to move value through time, space, and scale.

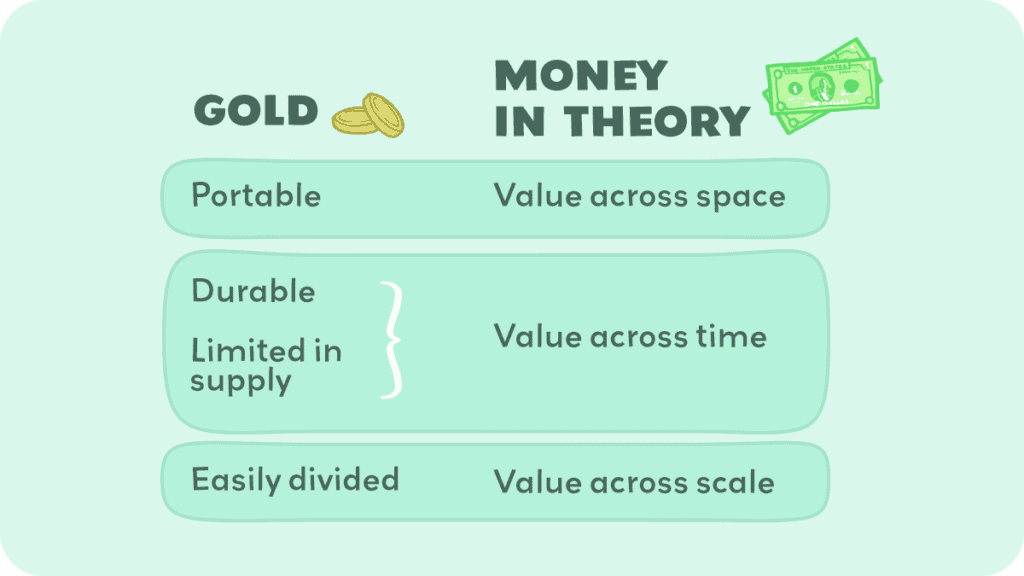

To this end, things that are effective as money tend to be portable, durable, and limited in supply. Traditionally, precious metals such as gold and silver are the most common sources due to how well they meet all three criteria. Today, these have largely been replaced by paper money. We’ll look more at that later.

First off, gold and silver are portable, making it convenient to use them as a means of exchange. It is far easier to carry around a sack full of gold than it would be to carry around a bunch of steaks, loaves of bread, or candles.

Gold can also be easily weighed and divided, or even stamped into standard gold coins by the government or other issuers.

Second, gold and silver are durable. The gold you have today will still be there a year from now; meanwhile, the steaks and bread from our simplified economy have long since rotted away, though the candles are probably still good assuming they haven’t been burned. The point is that for something to function effectively as money, it needs to be durable.

Finally, they are limited in supply and difficult to obtain. This provides a relatively stable supply of money, which allows them to be easily converted into prices for other goods and services. If, instead, you chose something like dirt or pebbles, it would be difficult to know how much to charge for whatever you’re selling since the monetary supply would be constantly shifting as people dig more dirt or search for more pebbles, leading to a rapidly expanding money supply and hyperinflation.

History Of Money

Traditionally, gold and silver have been the primary source of money, though in recent centuries this has given way to paper bills. Initially, this was done for convenience, as people found it easier to deposit their gold and silver in banks and conduct their day-to-day transactions with notes that showed ownership of that precious metal.

Anyone possessing that paper note could claim ownership of the metal. However, in 1971, the US government eliminated the link between paper money and the precious metal that had previously backed it, and the paper money we use today is what is called ‘fiat money’.

This is money that has no intrinsic value, but is money because the government says so, and everyone accepts this and goes along with it due to the benefits discussed throughout this post.

Our last hidden mystery of money is that it must be widely accepted. If your Memecoin is only accepted at your local grocery store, that’s great, but don’t expect to be paying your utility bill or taxes with it. One of the feedback loops of onboarding Bitcoin would be increasing adoption of its acceptance. As more and more people accepted it, it would become more useful as money.

In short, money is anything that people agree to accept as money, whether it’s paper money or the cigarettes used in prison, and provides a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account.

Though, theoretically, anything can be money, some things make better forms of money than others due to their portability, durability, and scarcity.