If you’ve ever traveled to a foreign country, there is a good chance you had to exchange currencies. Maybe you went to a currency exchange, or a bank, or changed it at the airport. The point is that most nations have their own currency that is accepted within their jurisdiction.

In this article, we will look at exactly what currency is, how it differs from money, and how different currencies relate to one another in terms of value.

What is Currency?

Currency is defined by the US Mint as “any kind of money – paper or coins – that’s used as a medium of exchange.”

There are a few things that the term “currency” implies. First is that it is tangible. As the definition states, it comes in the form of paper and coins. Other things—such as electronic transfers—do not qualify as currency, though the amount may be measured in the local currency.

The second thing is that generally speaking, currency is issued by the government or public authority of a particular jurisdiction. Different political territories issue different currencies. The eurozone issues the euro, the United Kingdom issues the pound, and the United States issues the dollar. Each currency has different denominations.

For example, the US Mint issues the following forms of currency:

- Coins:

- penny ($.01)

- nickel ($.05)

- dime ($.10)

- quarter ($.25)

- fifty-cent piece ($.50)

- dollar coins ($1)

- Bills or Paper Money:

- $1 bill

- $2 bill (though these are relatively rare)

- $5 bill

- $10 bill

- $20 bill

- $50 bill

- $100 bill

Additionally, there are $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000 bills that, though no longer issued, are still in circulation and redeemable at their full face value.

All currency in the United States was printed after 1861; any bills or coins from before this time are no longer valid.

Currency vs. Money

At this point, you may be asking if currency is just another term for money. In fact, the two terms are often used interchangeably; however, there are differences worth mentioning.

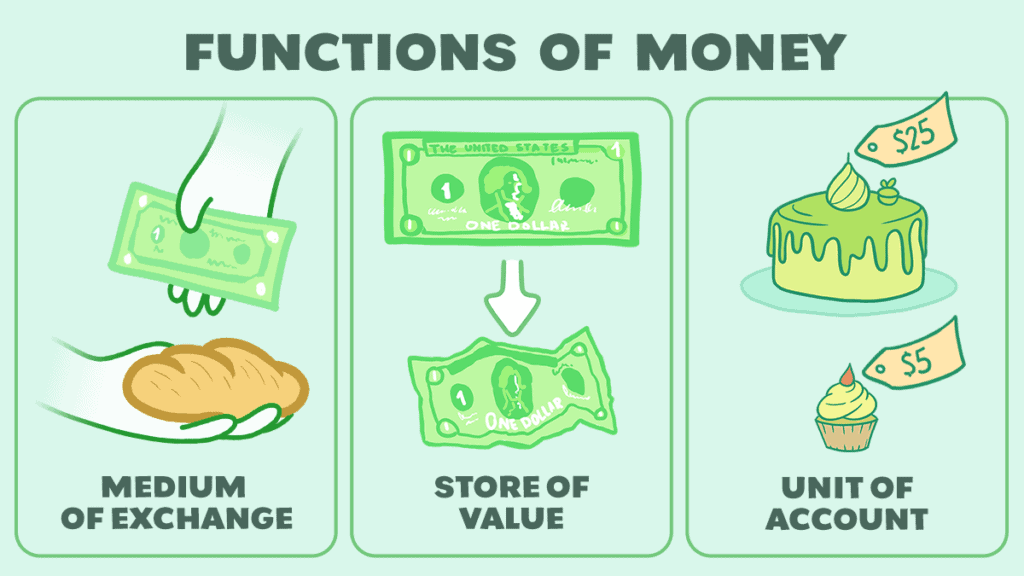

Basically, currency is money issued by a government of a specific jurisdiction, whereas money can take many forms. As such, all currency is money, but not all money is currency.

Think of it like the relationship between dogs and animals. All dogs are animals, but not all animals are dogs.

Another way of thinking of it is that currency is one, tangible form of money that is used as a medium of exchange.

Money is a broader term that refers to the intangible system of value that allows the exchange of goods and services to take place. Where currency refers to the paper notes and coins issued by a nation (currently, there are over two hundred national currencies in circulation), money can take a variety of forms.

How often have you purchased something or paid somebody with nothing physically changing hands?

When you write a check, use a debit card, or make an electronic transfer, you are spending money. That is, you are transferring the value agreed upon from your account to that of whomever you are paying. However, you are not using currency, as no paper bills or coins are changing hands.

Early Currency Exchanges

The earliest form of money was commodity money—that is, the use of items of value as a medium of exchange. Not surprisingly, the first forms of currency were issued from gold coins minted with a government seal.

Starting with the Kingdom of Lydia in the late 600s BCE, taking gold and turning it into standardized and denominated units eliminated having to weigh and divide the gold with each transaction and greatly facilitated trade both within and outside the Kingdom. This allowed trade to flourish, enriching the Kingdom of Lydia.

Fun fact: the saying “rich as Croesus” immortalizes this economic success by referencing the Lydian king who was said to possess legendary wealth.

Not surprisingly, then, this successful policy was replicated by others such as the Roman and Persian Empires. Specifically, as the Roman Empire came to engulf a number of provinces and client-states, the Romans developed a banking system that served both as a store of wealth and a currency exchange.

People who planned to travel throughout the Empire could take their money and store it at a bank, where they would be given a certificate of deposit. They could then travel to a different part of the Empire and use that certificate to withdraw the money without having to carry it with them.

Additionally, they could withdraw it in the local currency, getting the same value they deposited but in a different currency.

This function of banks played an important role in banking during the Middle Ages.

In fact, since exchange rates can fluctuate (more on that later), banks during the Middle Ages used currency exchanges to circumvent the Catholic Church’s ban on usury—lending money with high interest rates. By lending in one currency and taking repayment in another, banks could mask interest as differences in currency rates.

For example, say an Italian merchant wants to borrow a hundred Italian coins, which are worth the same as German coins. The bank could lend the merchant a hundred German coins, providing the same value as the hundred Italian coins.

When it comes time to repay, the merchant gives the bank two hundred Italian coins, doubling the value of what the bank lent him. However, the bank could claim that the Italian coins are only worth half of what the German coins are, thus justifying the amount of the repayment.

Keep in mind that, at that time, exchange rates were difficult for officials to verify; this wouldn’t be possible today.

Currency Exchange During the Gold Standard

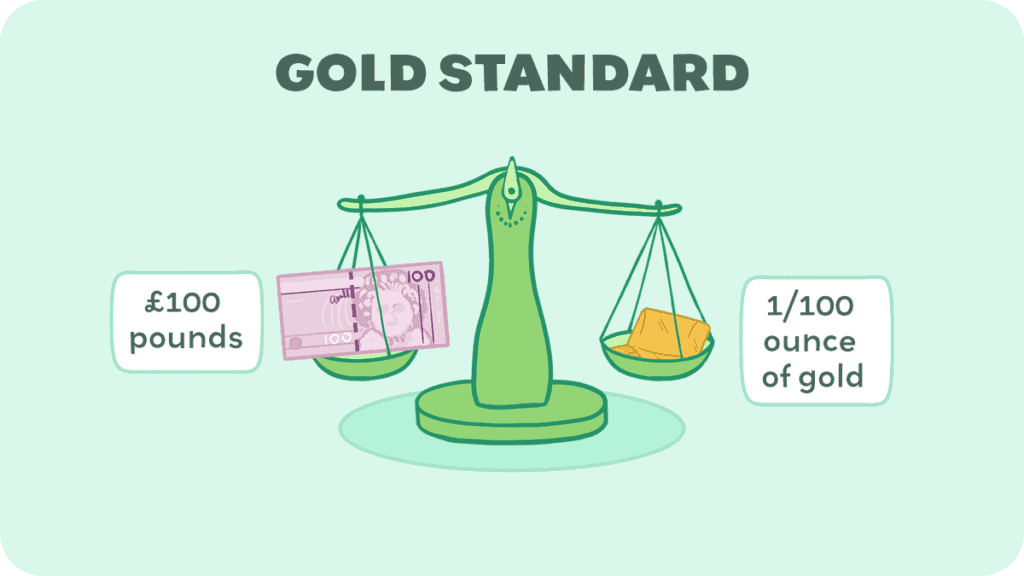

Starting with the United Kingdom, most countries adopted a gold standard by the 1870s. This meant that they would issue a currency—for example, pounds in England or dollars in the United States—backed by a certain amount of gold.

These currencies were a form of representative money—each denomination of a given currency served to represent a certain amount of gold. This development greatly facilitated currency exchange and encouraged international trade.

For example, say an ounce of gold is worth two British pounds. Additionally, say it is worth four French francs. If you were a British merchant wanting to trade in France, you could easily convert your pounds to gold in Britain, and then convert the gold back into francs once you arrived in France.

However, since we know that one ounce of gold equals two British pounds equals four French francs, we can cut out the middleman and exchange our British pounds for two French francs apiece.

This allowed goods and individuals to travel more easily across borders by allowing currencies to be easily converted, and helped trade flourish. It is for this reason that, though the gold standard fell apart during both World War 1 and the Great Depression, the Allied nations attempted to revive a similar system.

Bretton Woods and Fixed-rate Exchange

Following World War II, the Allied countries met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, US to develop a stable international monetary system that would allow trade to flourish once again.

Rather than simply return to the gold standard, they developed the Bretton Woods system. The US would remain on the gold standard, setting the price at $35 per troy ounce. However, the other nations would peg their currencies to the US dollar, ushering in the era of fixed exchange rates.

Say the UK set the pound to 1 pound/dollar, France set the franc at 2 francs/dollar, and Germany set the mark at 4 marks/dollar. This makes exchanging currency easy, as we would also know that:

1 pound = 2 francs = 4 marks

and

1 mark = .5 francs = .25 pound

This system once again eased currency exchange and allowed trade to ease post-war recovery efforts. It also marked a return to currency as a form of representative money, since ultimately each currency could be linked to gold.

This system continued until 1971 when the United States removed itself from the gold standard. The international supply of dollars had outpaced the United States’ supply of gold and, in order to prevent a run on gold, President Nixon delinked the dollar from gold.

This converted world currencies to fiat currencies—currencies backed by nothing of value that simply serve as money because of faith in the governments issuing them. It also ushered in the era of floating exchange rates.

How Floating Exchange Rates Work

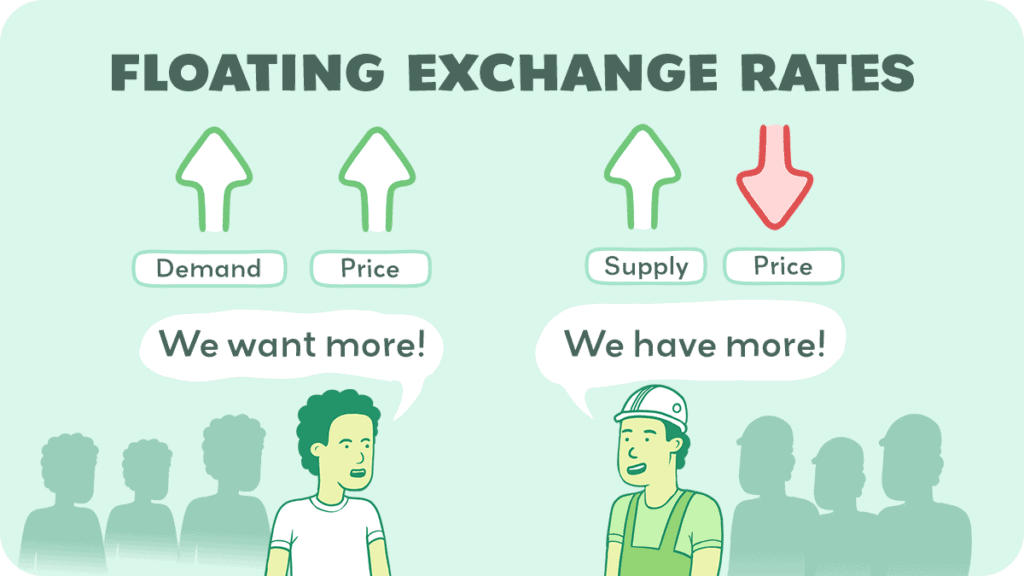

As opposed to fixed exchange rates, which are set by the government, the price of a currency with a floating exchange rate is determined by economic factors.

Currency is traded and converted on exchanges, like stocks and commodities, with people looking to buy and sell different currencies. Think of a currency like anything else—if you want to buy a British pound, you must pay X amount of US dollars (or another currency). Like many things economic, the amount that must be paid is determined by supply and demand.

Basically, demand is directly correlated with price—as demand for a given currency goes up, the price of that currency goes up, and vice versa. Likewise, an increase in supply is inversely correlated with the price of a currency—an increase in supply will cause a decrease in the price, and a decrease in the supply will cause an increase in the price.

However, what factors determine the supply and demand of a currency?

Factors Determining Exchange Rates

A major factor in the price of exchange rates is economic activity. If a nation is economically strong, more people across the world will want to buy its goods. This causes an increase in the demand for its currency, causing its price to rise relative to other currencies.

Another factor is the political situation of each nation. If a nation is politically unstable, people may fear that its currency will become worthless (remember, fiat currencies are backed by nothing other than the word of the issuing government). Thus, the demand for that currency will decrease.

The main factor in determining the supply of a currency is the national bank. If a nation wants to increase the supply of its currency (thus lowering its price on currency exchanges), it can increase the production of that currency. And, if it wants to do the opposite, it can buy that currency back.

Likewise, a nation importing a large number of goods will have an increase in supply as its citizens convert their currency to the currency of the nation from which they are importing goods (i.e. selling their currency). Additionally, citizens of a politically unstable country may wish to hold their money in currencies from more stable nations.

A final factor determining exchange rates in a floating system is speculation. Since currencies are bought and sold on exchanges, people will buy and sell currencies based on their anticipated future changes in value.

As with stocks, people hope to buy low and sell high. If traders are optimistic about a currency’s future value, the demand for that currency will increase as people hope to cash in. Likewise, if traders are pessimistic about a currency’s future, the price will drop as more people look to sell and fewer look to buy that currency.

Conclusion

To recap, a currency is a nation’s tangible form of money using different denominations to denote value. With over 200 national currencies in existence, you can trade your money from one currency to another, typically using a system of floating exchange rates.

However, though most nations switched to floating exchange rates following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, some like Saudi Arabia continue to peg their exchange rates to the US dollar.

Thank you for joining us in this overview of currency. We hope you enjoyed this article and invite you to join us again next time for another informative article on the world of finance.