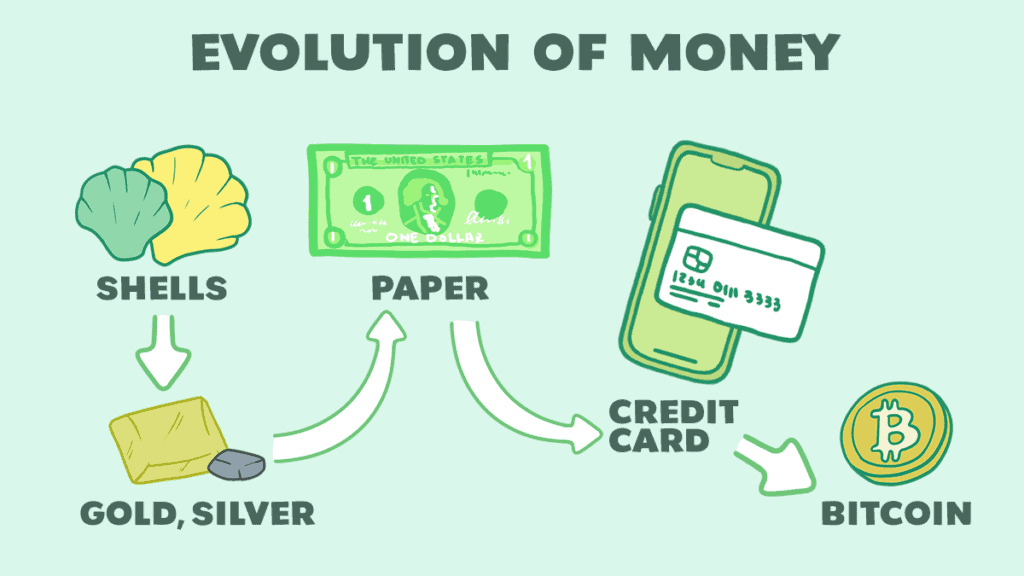

Money is such a central part of modern life that we often take for granted, but have you ever wondered how it came to be? In other words, who was the first person to decide that a piece of paper with a picture of a president could be worth something? How did we get from growing our own food to a society where we can purchase food with the swipe of a card?

In this article, we will explore the history of money – when it came into existence, why and how it started, and the various forms it’s taken throughout the centuries.

First, let’s clarify what money is. Money is anything that’s commonly accepted as a means of exchange, holds its value over time, and can be easily translated to express the cost of something. It is something that can be traded for goods and services and is widely accepted throughout society.

Barter System

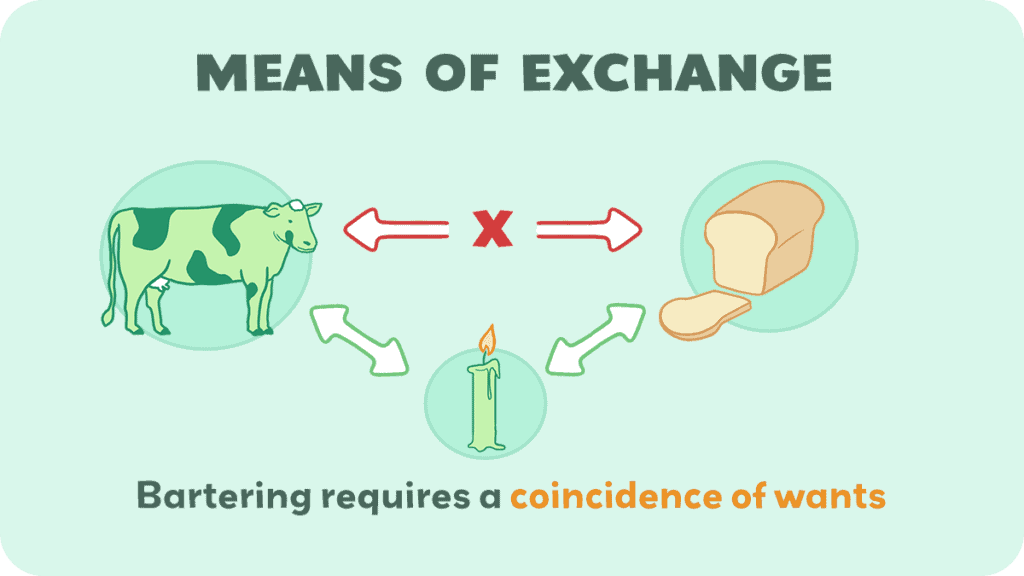

Before we had money, humans relied on a barter system to conduct economic activity. Simply put, this involved trading one good or service for another.

For example, I might agree to fix the roof of your house in exchange for a bag of rice or a loaf of bread. I might also demand several bags of rice or several loaves of bread, or you might try to give me a pair of shoes instead.

This illustrates some of the complications of the barter system.

First off, you must find someone who has something you want and wants something you have.

Second, you must agree on what constitutes a fair trade. I may think my roof-patching services are worth considerably more than the one bag of rice you are offering, or you may need the rice more than I do. This can make agreeing on a fair trade difficult.

In short, getting something in a barter system requires finding someone who has what you want, is willing to trade it for something you have (and are willing to give up), and will agree to acceptable terms for the trade.

This can make the entire process burdensome and confusing. This confusion is even worse when there are multiple people willing to trade. Should you accept a bag of rice for your roof-patching services, or patch the roof of the guy willing to give you an Xbox that exists for some reason in this primitive society?

Which deal is better may also vary depending on current circumstances. If food is plentiful, then the Xbox seems like a better deal; however, if there’s famine, it’s probably better to take the rice.

Additionally, say there’s some guy a town over who will offer two loaves of bread to patch his roof. Is this a better deal than the bag of rice, and is it a better enough deal to justify the added travel costs?

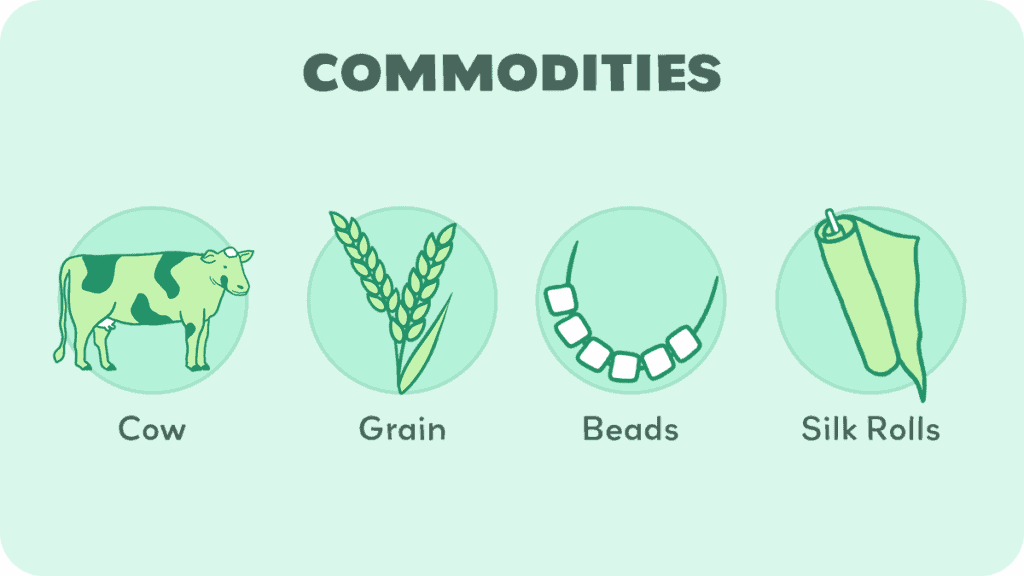

Commodity Money

To help quantify and simplify these decisions, early societies began using commodities such as cattle and, with the advent of agriculture, grain and other plant products between 9,000 and 6,000 BCE. Other types of commodities included:

- Salt

- Beads

- Animal skins

- Peppercorns

- Weapons

- Silk

- Cacao beans

- Barley

This allowed people to purchase goods and services without having to find somebody interested in the barter they were proposing. Instead, they could simply exchange the commodity for what they wanted, which could either be used directly or traded to a third party in turn.

This also provided a convenient way to measure wealth or the value of something. For example, if a family had 100 cows, you could infer they were relatively wealthy, whereas one possessing only a single cow was not. This could inform you whether or not entering into a marriage or another form of social covenant with them was in your best interest.

Cowry Shells

Cowries, shells from a mollusk found in coastal areas, were another form of early currency, and represent a major step in the development of money. They were first used in China, likely around 1200 BCE, and have been used in parts of Africa until recently.

Going back to the three functions of money, they could be used as a means of exchange as effectively as commodities but had the added advantage of being highly portable. It’s obviously much easier to carry a handful of shells with you than it is to bring several cows.

Additionally, shells are durable as opposed to commodities which are often perishable as cattle can die or plants can rot.

Finally, because they are small and relatively uniform, they can provide a more accurate unit of account. The shells all have roughly the same value, whereas cows or crops can vary widely in their quality and, thus, their value.

In sum, the shells worked better as money due to their durability, portability, and uniformity of value.

Precious Metals and Coins

As societies grew more complex, precious metals became more common as currency. This led to the minting of coins from these metals. The Lydians became the first Western culture to mint coins in the second half of the seventh century BCE when King Alyattes minted the first gold coin, the Lydian stater.

Meanwhile, in the east, China developed the first known minting site at Guanzhuang in the Henan Province where spade coins were struck beginning around 640 BCE.

In particular, Lydia’s system included a divisional table of coins in which one coin of the larger denomination was worth five of the next denomination, and so on.

This is similar to the system in the modern United States, where one hundred pennies are worth twenty nickels, ten dimes, four quarters, or one dollar.

The divisibility of currency greatly facilitated trade both internal and external, helping make Lydia one of the richest empires in Asia Minor, and was replicated by future empires such as the Persian Empire and the Roman Empire.

Here are a few examples of ancient currencies minted from precious metals:

- Drachma (Greece)

- Tyrian shekel (Lebanon)

- Stater (Lydia)

- Daric (Persia)

- Talent (Rome)

- Ma’ah (Israel)

Paper Money

Though coins made from precious metals worked well as money, there was one problem – they could get heavy. This was a major consideration in the development of paper money.

The first paper money arose in China when the Yuan Dynasty moved to paper money in 1260 CE. However, in Europe, metal coins remained the primary source of currency until the 16th century.

At this time, colonial acquisitions allowed European governments to mint greater and greater quantities of coins due to their newfound sources of precious metals.

As the money supply grew, people began to find it more convenient to deposit their wealth in banks. The banks would issue notes proving ownership of the coins or precious metals, which depositors could then carry around and use to conduct their day-to-day transactions.

At any time, the individual holding the note could return to the bank and use it to claim the precious metal backing the note.

This marks the emergence of representative money. With representative money, though the paper money itself holds no intrinsic value, it represents something of intrinsic value directly tied to and supporting the paper money.

It should be noted that, at this time, paper money is still being issued by banks and private institutions rather than governments, as would occur later.

The first forms of paper money issued by European governments were actually issued by their colonial governments in North America. Due to the long voyage between the continents, colonial governments would often run out of cash before they could be resupplied by their home government.

Since they still needed to pay salaries and purchase supplies, they would issue what were essentially ‘I Owe You’s (IOUs), guaranteeing future payment by the government. Those receiving these IOUs would then exchange them for the goods or services they wished to purchase.

The first example of this was in 1685 when the French government in Canada issued playing cards signed by the Governor to use in lieu of French coins.

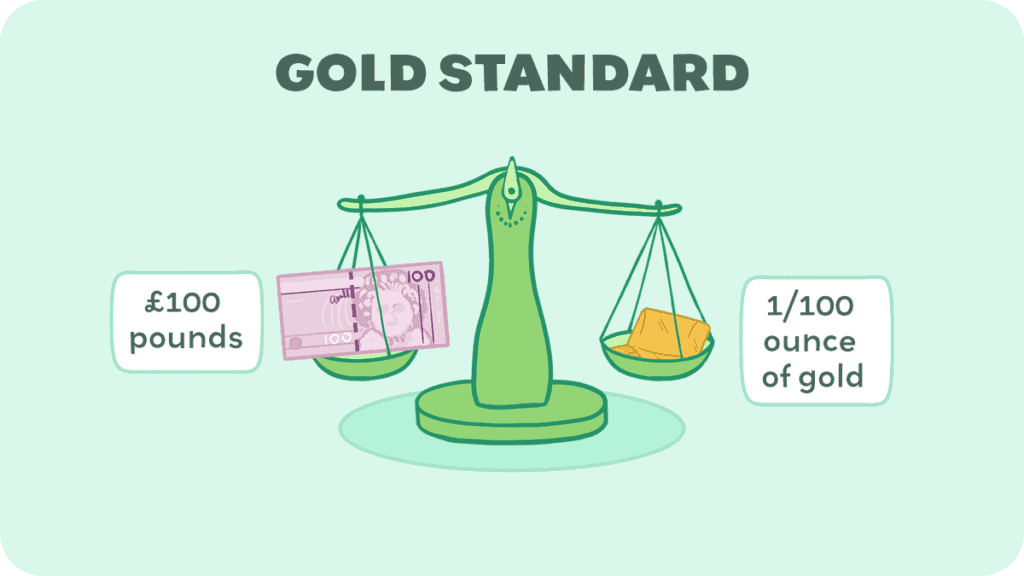

Gold Standard

This concept of representative money ultimately gave rise to the gold standard in which each country issued currency linked to a specific amount of gold. In other words, a specific unit of that nation’s currency is backed by a specific amount of gold.

For example, if the British government sets the price of gold at £100 an ounce, then one pound is worth 1/100 an ounce of gold. First put into practice in the United Kingdom in 1821, this standard was slow to spread as other countries continued to use a bimetallic system, backing their currency with a combination of gold and silver.

However, it took off in the 1870s as many other countries, including France, Germany, and the United States, adopted the gold standard following the discovery of gold deposits in North America. Because all currencies were linked to a common metal backing them, this made it easier to exchange currencies and conduct trade across borders.

During World War 1, many governments left the gold standard, printing inconvertible paper money to meet their demand for cash. This allowed governments to print enough money to meet their demand.

Following the war and the punitive Treaty of Versailles, the Weimar Republic’s decision to continue printing money in order to meet the needs of the struggling government led to the hyperinflation of 1923 that heralded the collapse of the Republic.

Though interrupted by World War 1, the gold standard was readopted following the war and back in full effect by 1928. However, the gold standard again collapsed during the Great Depression. The demand for money by governments struggling to deal with the crisis outstripped the supply of gold.

The gold standard began to erode in 1933 when the United States’ President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6012 which outlawed the possession of gold by private citizens. By 1937, no country remained on the gold standard.

Bretton Woods Agreement

Following World War II, forty-four Allied countries got together to attempt to devise an international monetary system that could maintain economic security. This led to the Bretton Woods Agreement.

Under this agreement, signatory countries would peg the value of their currency to the US dollar, setting up a system of fixed exchange rates. The dollar, in turn, would be fixed to the price of gold.

To ensure they remained at the agreed-upon rate, each country would keep a certain amount of dollars in reserve. This would allow them to buy or sell their own currency as needed to maintain the value of their currency against the dollar.

The agreement also set up the International Monetary Fund to monitor exchange rates and ensure countries kept enough US dollars in reserve to maintain their set rate.

The important point is that each nation’s currency was worth a certain number of US dollars which, in turn, were worth a certain amount of gold – $35 per troy ounce, to be exact.

However, by 1960, the US government didn’t have enough gold to cover the worldwide supply of dollars as it had ballooned due to US foreign aid, military spending, and foreign investment. This continued for a decade until, in August 1971, President Nixon decoupled the US dollar from gold.

The end of the convertibility of the dollar into gold changed the exchange of currencies from a fixed rate to a floating rate, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. It also turned the US and most other currencies into their present form – fiat money.

Fiat Money

Fiat money is similar to representative money except that it isn’t backed by gold or anything else of value. Its value is based on the backing of the government that issued it.

In essence, it is money because the government issues it and people trust the government enough to accept it. The value of any given fiat currency is determined by the supply and demand of a specific currency compared to other currencies and determined by economic events and central banks.

In this system, central banks play a key role in controlling the value of their currency through controlling interest rates and the money supply.

The rise of fiat money has also paved the way for digital currency. These are transactions that occur entirely online, taking place electronically with no physical representations ever changing hands.

Instead, they are logged by verified financial institutions. It has also led to the emergence of cryptocurrencies, starting with Bitcoin in 2008. Rather than being issued by a central government, transactions using this currency are recorded on a public blockchain using public computers worldwide.

Digital transactions have become so common that some countries such as Sweden, Bahamas, and China are even considering issuing a national digital currency called CBDCs – Central Bank Digital Currencies.

I hope you found this informative and that it helped you understand the various forms that money has taken throughout the ages.