You’ve probably heard of the barter system at some point in your life. Whether it was in a history class as a child or an economics course, you are familiar with this early form of commerce. Even if you aren’t, the name is pretty self-explanatory.

A barter system is an economic system in which people trade, or barter, items directly with one another without the use of money.

You may also be aware that money in various forms quickly replaced the barter system, dating almost as far back as civilization itself. Why? If people can simply trade for what they need, why go through the extra step of using money as a middleman?

The answer is that the barter system has many problems that money helps solve. In this article, we’ll examine some of these problems and how money helps solve them.

What is Money?

To provide a lens through which to view these problems, let’s start by briefly looking at what money is and what items are effective as money.

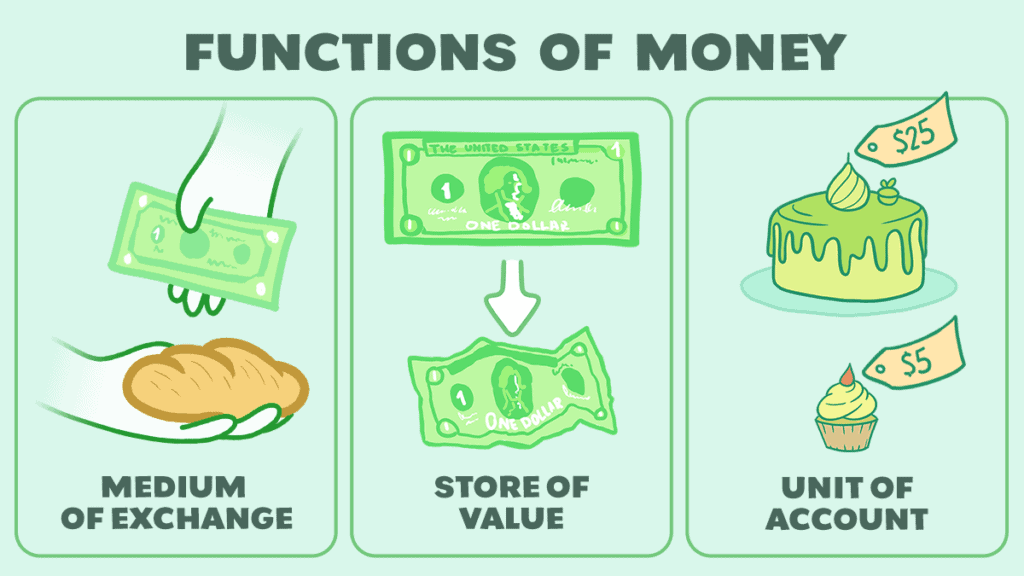

In short, money is anything that serves as:

- A medium of exchange

- A store of value

- A unit of account

Anything that serves these three purposes can be money. Throughout history, things as diverse as tea, salt, cowry shells, and gold have all been used as money. To make an effective form of money, an item should have four traits:

- Rarity

- Portability

- Divisibility

- Durability

For this reason, gold and other precious metals became the most commonly used form of money throughout history, up until the arrival of fiat money.

What is a Barter System?

We have a whole article about bartering, but most simply, if you need something, you find someone who has it and work out a trade with them.

This could be a trade of simple objects, or a trade of skills or service.

For instance, bartering could look like fixing someone’s computer and they fix your roof. It could also look like trading bread for furs. Any exchange of goods or services that have intrinsic value—meaning they are valuable on their own, even if there isn’t a specific value assigned—counts as bartering.

The opposite of something with intrinsic value is extrinsic value, which could be something like paper money that the government says has a value even though it isn’t particularly useful if people stop accepting it as payment.

Okay, so we know what bartering is. Let’s look at some of the problems with it.

Bartering Problem #1: Deferred Payments

The first problem is the difficulty of making contracts for the future. This is because many goods that can be traded are perishable or vary in quality.

For example, if you want to buy an ox today to plant your crops, you could offer to give a portion of your harvest in six months for the ox today.

However, there is no guarantee that the harvest won’t be ruined by pestilence or that you won’t give the owner of the ox the worst of your crops, saving the best for yourself.

Similarly, if I offer to shovel your driveway this winter in exchange for food today, you have no guarantee that I’ll follow through or that I won’t do a poor job of it.

Note that this does not make future payments or contracts impossible. However, they must be stated in very specific terms, and there could be a dispute in the quality of the good or a change in the value of the good.

Because money is durable, holds its value, and comes in specific, fungible units, money helps ease these problems though the risk of default or inflation is still present.

Bartering Problem #2: No Common Value

We use inches or centimeters to measure length; we use pounds or kilograms to measure weight. What do we use to measure value? Money.

The barter system lacks a common measure of value—therefore, it can be difficult to know how much something is worth to an individual.

Imagine walking into a store and asking how much the ring in the window is. If we are in a barter system, how would the store clerk respond? They might say something like “it’s worth a car,” but cars vary greatly in value.

If they say “1,000 gallons of milk,” they might value milk more than you (or someone who’s lactose intolerant). And what’s worth more—the one-car ring, or the 1,000-gallon ring?

The point is that, with no standard unit of account, the simple question of, “How much does that cost?” becomes quite complicated.

Money solves this problem by serving as a unit by which to measure the intangible quality of value. This makes conducting business much simpler. The store clerk can simply respond that it’s worth X amount of gold or a certain number of dollars and cents.

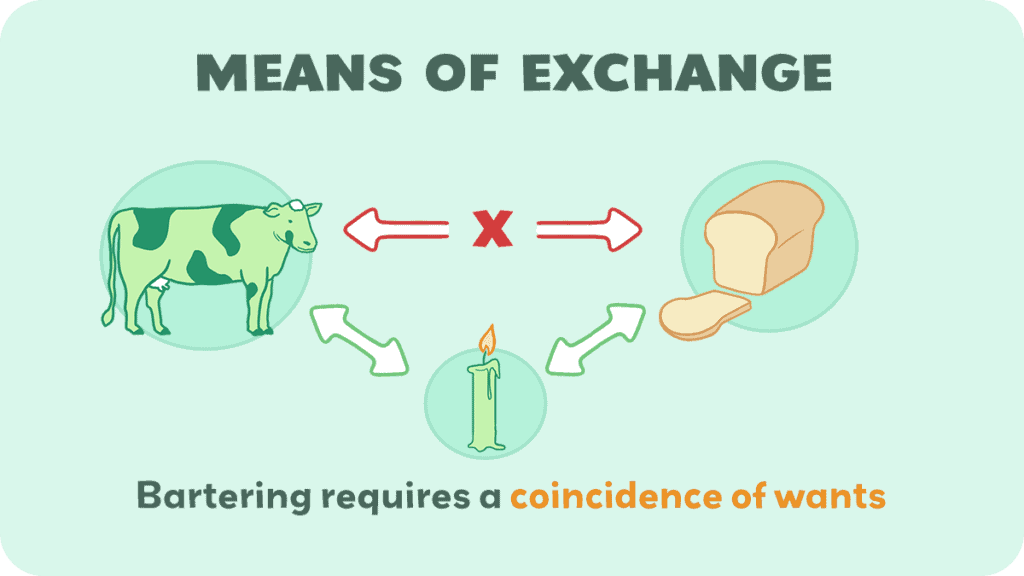

Bartering Problem #3: Coincidence of Wants

Say you want to buy a new pair of shoes. You’ve heard of a new cobbler in town who is supposed to make excellent shoes, so you decide to check him out. You head to his store and find the perfect pair of shoes. You go to check out and ask what you can give him in return.

He wants a new belt. You tell him you don’t make belts, and you can’t very well give him yours because you prefer your pants around your waist. You tell him you’re an accountant and offer to do his books, but he already has a bookkeeper.

He says he’ll take a loaf of bread, but you didn’t bring any and, besides, you’re already unsure if you have enough for yourself. Ultimately, despite having the perfect pair of shoes and a willing seller, you leave shoeless.

Money solves this problem by acting as a medium of exchange. Even though you have nothing the cobbler wants, you simply give him money, which he can exchange for whatever he wants.

In this case, he gives you shoes, you give him money, and he gives that money to a belt-maker for a new belt. The cycle continues as such, and everybody wins.

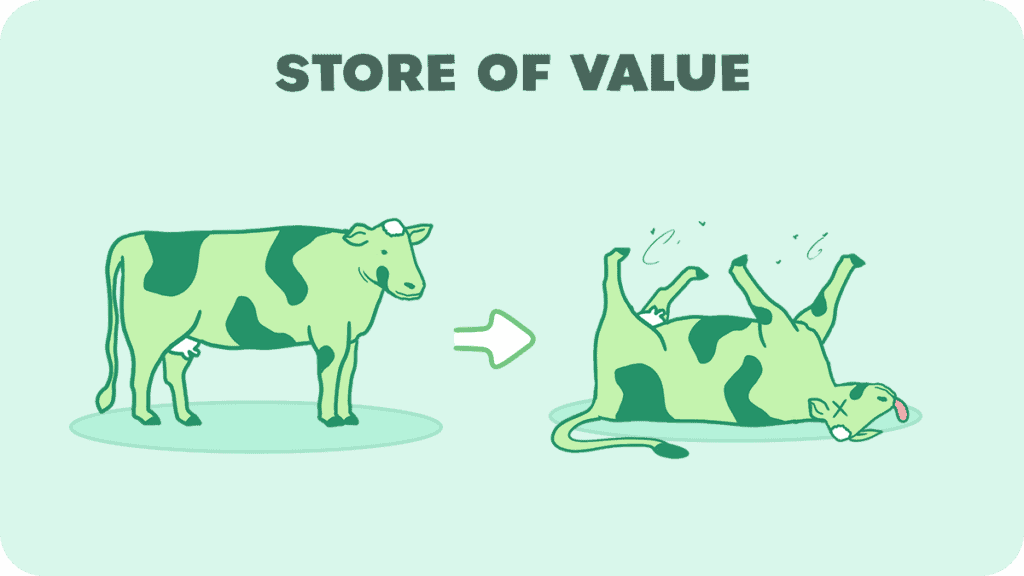

Bartering Problem #4: Inability to Store Wealth

Pretend you’re a strawberry farmer. You are excited because you have a wonderful crop of strawberries.

You take them into town and exchange them for a new pair of clothes, use them to pay someone to patch your roof, and buy other types of food so you don’t have to eat strawberries for every meal. At the end of the day, however, you still have more than half your harvest left.

What do you do? You’ll probably eat as much as possible, but you can’t eat all of it. You have nothing else you want to buy with it.

You’d like to store it to spend later as the need arises, but if you do that, it will perish. Though you are wealthy today, tomorrow you will be poor, and you have no way to hold onto that wealth.

Money solves that problem by acting as a store of wealth since it is usually durable. You simply sell the strawberries before they rot in exchange for money. You can then hold onto that money until you need it.

Bartering Problem #5: Transporting Goods

Say it’s Saturday and you want to do some shopping. You’re preparing to go to the market. If you live in a barter system, what do you bring with you? After all, you might know what you want, but you have no idea what the seller is going to ask for in exchange.

Even if you do, what do you do about the possibility that something catches your eye? After all, one of the goals of shopping is to shop around—who knows what you’ll find? That’s part of the fun, isn’t it?

This is complicated even more by the fact that some of the most commonly traded items in a barter system are necessities such as crops and livestock.

Do you really want to take all your cows with you every time you go to the market? Even if you know that you intend to trade them, carrying bushels of wheat or multiple heads of cattle isn’t exactly convenient.

Money solves this problem by acting as a common medium of exchange. This way, all you have to take is your money, and you can trade it for whatever you like.

Additionally, effective forms of money are portable. Think of the money in your pocket—much more convenient to carry with you than a cow, isn’t it?

Bartering Problem #6: Divisibility of Goods

You’re off to buy a new car. You arrive at the car dealership, find the car you want, and approach the dealer. You ask him how much and he says it is one cow.

You think that’s overpriced, so you haggle a bit, arguing that the car is only worth half a cow. After some discussion, he agrees. In principle, you’ve agreed to trade him half a cow for his car.

Now what? You could cut a cow in half, but that would presumably diminish the value of the cow. Besides, which half would he get? You could expand the trade to one cow for two cars, but what do you need with a second car?

Ultimately, you have to overpay him a whole cow for something that you agree is only worth half that (or accept a superfluous car).

The divisibility characteristic of money solves this problem because money can be divided into smaller and smaller units, such as dollars and cents. If you have a one-pound gold bar and agree to the price of half a pound, you can cut the bar in half and weigh it.

Emergence of Commodity Money

From these examples, I hope that it’s easy to see how commodity money such as gold came about early on in the history of commerce.

Once trade became commonplace, it didn’t take that much ingenuity for someone looking to sell an item to accept as payment something that they didn’t necessarily need with the intent to trade it to someone else at a later date.

For example, say you’re an accountant. Somebody wants to pay you for your services but has nothing you want. Do you simply turn them away? In all likelihood, you would accept something that you knew other people wanted with the intent to trade it at a later date.

Once people widely began accepting certain commodities, such as shells and beads, as payment, commodity money evolved.

Conclusion

It should be noted that, though there are problems with the barter system, the emergence of money didn’t render it obsolete. It is still used in certain circumstances today.

After all, one of the biggest problems is finding a double coincidence of wants —however, where this coincidence exists, direct trade is often most efficient (assuming the wants have roughly equal value—you don’t want to go trading the family cow for a handful of beans except for in one very specific, fictional situation).

We hope you enjoyed this article. If you found it interesting and informative, we invite you to subscribe to see other articles on similar topics. Thank you for joining us, and have a wonderful day or evening.